Conversation Starters About Vaping

FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS AND OTHER ADULT ALLIES SUPPORTING YOUTH

You can help youth make informed decisions about the use of vaping products. The following is information you can use to have ongoing meaningful discussions with young people about the effects of vaping.

- Not An Experiment offers information and resources tailored to youth, Educators, and Parents.

- Ophea’s Conversation Tip Sheets and Vaping Education Resources support educators in having conversations about vaping with students.

- School Mental Health Ontario’s Fact Sheets provide an excellent overview of vaping, curriculum links and best practices to support elementary and secondary educators in having informed conversations with students about vaping.

BUT FIRST… THE BASICS

Vaping is the act of inhaling and exhaling an aerosol produced by a battery-operated device that uses e-liquid (also called e-juice). The main substances in these vaping solutions are vegetable glycerine and/or propylene glycol, which are commonly mixed with a variety of flavourings. They can also contain varying levels of synthetic or tobacco derived nicotine. Vaping devices may also be designed to heat other substances, such as oils, dried cannabis, cannabis concentrates, etc.

Vapour products come in many shapes, sizes, and styles, some resembling beauty products or USB sticks. They have many names such as vapes, tanks, mods, or electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). They may also be known by various brand names. Products are packaged and marketed in a way that appeals to youth.

Vapour products are widely available in convenience stores, vape shops and online. In Canada, e-cigarettes, e-liquid and cartridges/pods are controlled by federal and provincial restrictions. Measures continue to be put in place as we learn more about e-cigarettes, including that they are NOT as harmless as the industry would have us believe.1

Several tobacco companies have invested in the vapour product market. Big Tobacco, since it has existed as an industry, has been bending the truth, faking their science, endorsing other people to lie for them, and employing countless other questionable practices for the purpose of profiting from a highly addictive product. You and the youth in your life can learn more about the industry from Not An Experiment; check it out!

According to the 2023 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS), about 11% of students report vaping in the past month and 4% report vaping on a daily basis.

CONVERSATION STARTERS

Not all vaping products contain nicotine… But most of them do, and their levels of nicotine vary widely.

IN FACT:

Vaping may expose those who vape to nicotine, which is highly addictive. Many e-liquids have levels of nicotine similar to or higher than cigarettes.

Children and youth are especially vulnerable to the effects of nicotine. They can become dependent on nicotine quicker than adults. Nicotine can alter their brain development, can affect memory and concentration, and may predispose them to other drug addictions.3

There is substantial evidence showing that vaping can lead to symptoms of dependence and addiction.4 There is also evidence that e-cigarette use can increase the risk of smoking cigarettes among youth and young adults.5

Vaping without nicotine is still toxic due to the presence of other chemicals and particles in the resulting aerosols.

Nicotine addiction causes stress.

IN FACT:

Among youth, the top reasons for trying vaping are curiosity and to reduce stress. However, nicotine addiction causes stress. Cravings for nicotine feel stressful because your body begins to go through withdrawal.6

Initially, vaping can feel good because nicotine stimulates the production of dopamine in the brain. Vaping can also create social opportunities to bond with other people who vape and could be a distraction from stressful situations. These factors can be motivation to continue vaping.7

The initial feel-good effect of nicotine wears off within a few hours and can lead to a desire to vape again. A person experiencing this nicotine withdrawal may have cravings or urges to vape. They can feel irritated or upset, anxious or depressed, jumpy, or restless and have difficulty concentrating. They may also notice changes in sleeping and eating habits.7

Over time, it can take more nicotine used more often to get any feel-good effect or to make the symptoms of withdrawal go away. This is called nicotine dependence. Eventually, what started out as vaping to get a feel-good experience turns into vaping to get rid of withdrawal symptoms.7

This cycle can make it feel like vaping nicotine relieves stress. But the reality is that it only makes withdrawal symptoms go away and the cycle continues.7

The best way to deal with stress is to identify what is causing anxious feelings. It’s how we react to situations, thoughts and feelings that can make a difference in our mental and emotional well-being.

Less harmful doesn’t mean harmless.

IN FACT:

Vaping products expose people who vape and bystanders to toxic substances, but at lower levels than tobacco smoke.4 However, less harmful doesn’t mean safe.

Vapour product use can cause light-headedness, throat irritation, coughing, and increases in heart rate and blood pressure. The aerosol produced by the heating process inside the vaping device is a mixture of chemicals, including carbonyls (formaldehyde, acetaldehyde), volatile organic compounds, metals (tin, silver, nickel, aluminum, chromium, lead) and particulate matter (fine, ultrafine particles) that can hurt the lungs.8 Propylene glycol and flavourings are generally safe to eat, however, inhaling them into the lungs has been linked to lung disease.9, 10, 11 The high-dosage levels of nicotine provided by vapour products can also have harmful effects on cardiovascular health.12 Further long-term health impacts remain unknown.

Vaping is not safe. There is broad scientific consensus that anyone who does not smoke, should not vape.

In addition, an individual’s exposure to toxic and cancer-causing chemicals is only reduced if they switch completely from cigarettes to e-cigarettes. Many end up continuing to use both.

Vapes can be a tool to help people who smoke quit… But it’s not as simple as it sounds.

IN FACT:

To date, no vapour product has been approved by Health Canada for use as a smoking cessation aid.

The evidence about e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid is limited. More research is needed on the effectiveness of vapour products as a tool to help youth quit smoking.

The Eastern Ontario Health Unit (EOHU) recommends that people who want to quit smoking use approved medication (e.g., varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion) and counselling, either alone or in combination. Nicotine replacement therapy products include the nicotine inhaler, patch, lozenge, gum, and mouth spray.

When approved medications don’t work, vapes can help some people quit smoking cigarettes.

Many people who vape want to quit. The current approaches for tobacco cessation, those recommended by the EOHU above, can be adapted and used for vaping cessation as well.

Sharing vapes with youth or vaping at school can cost you.

IN FACT:

There are reports of youth vaping in schools as the aerosol cannot be easily detected, does not set off fire alarms, and is easier to conceal from adults and authorities.

Youth also report vaping cannabis for the same reasons.

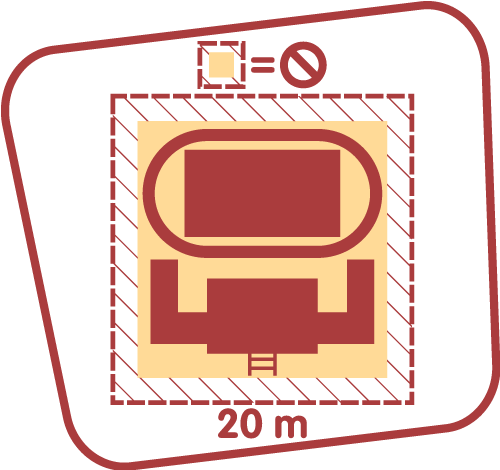

The Smoke-Free Ontario Act 2017 (SFOA) prohibits the use of e-cigarettes in all the same areas where smoking tobacco is already banned. This includes anywhere on school property (indoors and outdoors) and within 20 metres from the perimeter of the school grounds, as well as all enclosed public places and workplaces.

It is also against the law to give or sell vapour products to youth under the age of 19 in Ontario. The fine for supplying a vapour product is $490. The fine for vaping in a prohibited area is $305.

Health Canada’s campaign can help you and the youth in your life further consider the consequences of vaping.

Support Is Available for Youth Who Want Help to Quit Smoking or Vaping. Along with talking to a healthcare provider for support and advice, youth can check out Quash, a judgement-free app to help you quit smoking or vaping — the way you want!

CONTACT US

Schools can communicate with the EOHU School Health team by sending a message to schoolinfoecole@eohu.ca. Parents are welcome to communicate with the EOHU by telephone or email:

- 1-800-267-7120

- info@eohu.ca

(Emails are monitored Monday to Friday during regular office hours. Please provide a phone number where you can be reached during the day).

References

- Guidance on Vaping Products not Marketed for a Therapeutic Use. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2019 Jan 15 [cited 2020 Jan 31].

- Ontario Student Drug Use Health Survey, 2021.

- Health Canada (Risks of Vaping Webpage).

- Vaping products including e-cigarettes Evidence summary, current as of January 2, 2020. Toronto: Population Health and Prevention, Prevention and Cancer Control; 2020 Jan 2 [cited 2020 Jan 31].

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM): The Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes: A Consensus Study Report of the NASEM. 2018.

- Reduce Your Stress, Smokefree.gov, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Nicotine use and stress. Truth Initiative; March 2022.

- Pisinger, C., & Døssing, M. (2014). A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Preventive Medicine, 69, 248–260.

- Fowles, J. R., Banton, M. I., & Pottenger, L. H. (2013). A toxicological review of the propylene glycols. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 43(4), 363–390.

- Rose, C. S. (2017). Early detection, clinical diagnosis, and management of lung disease from exposure to diacetyl. Toxicology, 388, 9–14.

- Clapp, P. W., Pawlak, E. A., Lackey, J. T., Keating, J. E., Reeber, S. L., Glish, G. L., & Jaspers, I. (2017). Flavored e-cigarette liquids and cinnamaldehyde impair respiratory innate immune cell function. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 313(2), L278–L292.

- Neal L. Benowitz & Burbank (2016). Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016 August; 26(6): 515–523. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2016.03.001