Self-Directed Learning for Professionals and Allies: Supporting People in Their Vaping Cessation Journey

You can help people make informed decisions about the use of vaping products. The following is information you can use to support them in their cessation journey when they are ready.

On this page:

- Vaping: The Mechanics

- Effects of Nicotine

- Health Effects of Vaping

- History and Marketing of Tobacco Industry Products

- Why People Vape

- Populations of Concern

- Vaping Cessation Guidance

- Vaping Cessation Tools and Techniques to Support Someone in Their Cessation Journey

- Additional Resources

- Additional Information

Vaping: The Mechanics

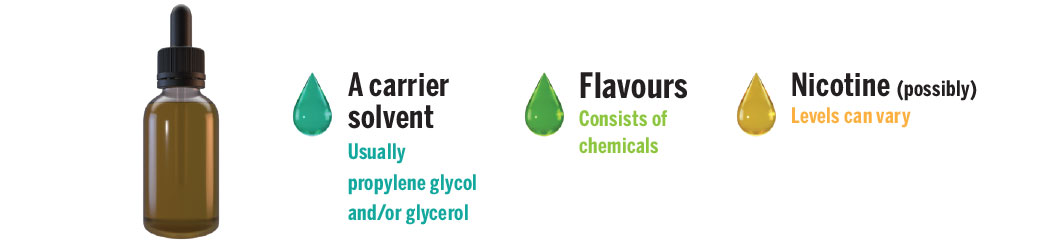

Vaping is the act of inhaling and exhaling an aerosol produced by a battery-operated device that uses e-liquid (also called e-juice). The main substances in these vaping solutions are vegetable glycerine and/or propylene glycol, which are commonly mixed with a variety of flavourings (chemicals). They can also contain varying levels of synthetic or tobacco-derived nicotine. Vaping devices may also be designed to heat other substances, such as oils, dried cannabis, or cannabis concentrates.

There are four main components to a device: a battery, a mouthpiece, a heating element, and a chamber such as a tank or reservoir to contain a vaping solution. The devices come in many shapes, sizes, and styles. They have evolved from cigarette and pen look-a-likes to devices resembling beauty products or USB sticks. They have many names such as vapes, tanks, mods, or electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). They may also be known by various brand names.

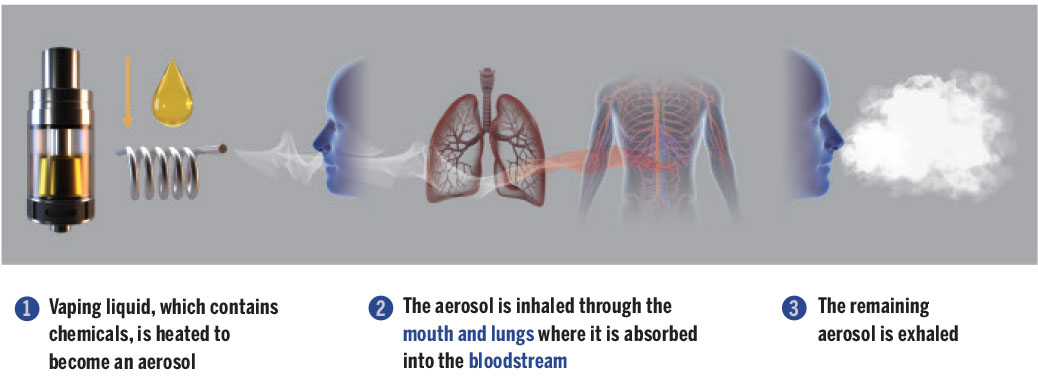

The heating process inside the vaping device produces an aerosol containing chemicals, including carbonyls (formaldehyde, acrolein, acetaldehyde), volatile organic compounds, metals (tin, silver, nickel, aluminum, chromium, lead) and particulate matter (fine, ultrafine particles) that can hurt the lungs. This aerosol is inhaled through the mouth and lungs where it is absorbed through the bloodstream, and the remaining aerosol is exhaled.

Video: The Mechanics of Vaping

Components of a Vaping Device

Contents of Vaping Liquid

How it Works

Check out Vaping: The Mechanics infographic on Health Canada's website. For more information about vaping, check out Canada.ca/vaping.

Effects of Nicotine

Nicotine is addictive, whether it is synthetic (made in a lab), or tobacco-derived (from the plant). Nicotine is in products like cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, hookah and most vaping liquids, many of which have levels of nicotine similar to or higher than cigarettes.

Children and youth are especially vulnerable to the effects of nicotine. They can become dependent on nicotine quicker than adults. Nicotine can alter their brain development and affect their memory, concentration, and self-regulation. It may also predispose them to other drug addictions. [1]

Among youth, the top reasons for trying vaping are curiosity and to reduce stress. However, nicotine addiction causes stress. Cravings for nicotine feel stressful because your body begins to go through withdrawal. [2]

Initially, vaping or smoking can feel good because nicotine stimulates the production of dopamine in the brain. Vaping can also create social opportunities to bond with other people who vape and could be a distraction from stressful situations. These factors can be a motivation to continue vaping. [3]

However, the initial feel-good effect of nicotine wears off within a few hours and can lead to a desire to vape again. A person experiencing this nicotine withdrawal may have cravings or urges to vape. They can feel irritated or upset, anxious or depressed, jumpy, or restless and have difficulty concentrating. They may also experience changes in eating and sleeping habits. [3]

Over time, it can take more nicotine used more often to get any feel-good effect or to make the symptoms of withdrawal go away. This is called nicotine dependence. Eventually, what started out as vaping to get a feel-good experience turns into vaping to get rid of withdrawal symptoms. [3]

This cycle can make it feel like nicotine relieves stress. But the reality is that it only makes withdrawal symptoms go away and the cycle continues. [3]

Health Effects of Vaping

Acute (short-term) health effects reported by people who vape include light-headedness, throat irritation, dry mouth, dizziness, coughing and increases in heart rate and blood pressure. Vaping has also been linked to cases of acute lung illness, some of which have been fatal. [4]

As explained in the section above, chronic exposure to the high levels of nicotine in e-liquids can alter brain development among youth, affecting their memory, concentration, and self-regulation. [1]

Although the levels of toxic chemicals in e-cigarette aerosols are lower than those in the smoke of combustible tobacco, a “safe level” of exposure has not yet been established. Studies show that long-term exposure to toxic chemicals like aldehydes (including acrolein, acetaldehyde, and formaldehyde) found in aerosols of e-cigarettes can cause lung disease (COPD, asthma, lung cancer), as well as cardiovascular (heart) disease. [5] Because the products are relatively new, not all long-term health effects are known. [1]

History and Marketing of Tobacco Industry Products

Half of Canadians smoked in the 1960s. At the time, smoking had been normalized because tobacco marketing was embedded in so many aspects of life. It took over 50 years to massively reduce smoking rates in Canada, and now 10% of Canadians across all age groups smoke. In 2021, 4% of youths aged 15 to 19 smoked. Campaigns challenged what was seen as normal back then, and groups advocated for changes including smoke-free legislation, tobacco taxes, and restrictions on marketing and youth access.

With the decline in smoking rates, tobacco companies had to recruit new customers to replace the ones who either passed away or quit smoking. They therefore introduced new vapour products designed to entice new customers, and further engage current customers.

Vaping devices entered the Canadian market in 2004. At the time, e-cigarettes containing nicotine were not legal in Canada. However, the ban was never enforced and e-cigarettes, both with and without nicotine, continued to be promoted and sold across the country.

By 2012, tobacco companies had begun buying vape brands or developing their own. In 2018, it became legal to sell e-cigarettes with nicotine to Canadian adults, but regulations didn’t go far enough in preventing youth from using vaping products.

Today, we see vapour products being marketed in very familiar ways – as products that are normal to consume because “everyone is doing it.” Ads normalizing vaping are especially targeting young people. As was the case for tobacco products years ago, the marketing of vapour products glamourizes the behaviour and minimizes the harmful effects. This marketing is coming from the same industry that, in 1994, lied under oath while testifying, saying that they believed nicotine was not addictive.

Celebrity endorsements, thousands of e-liquid flavours, colourful and appealing packaging, advertisements associating the use of the products with beauty, fun, vitality, and various cultural identities, all contributed to the gain in popularity of vapes, not to mention the sleek and modern designs of the vapes themselves and youth-centered paraphernalia.

Why People Vape

The 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) suggests that most young people are not vaping for the purpose of reducing or quitting smoking. Results indicate:

- Many reported vaping to reduce stress – 33% among youth aged 15 to 19, and 18% across all ages.

- Youth aged 15 to 19 who reported having vaped in the past 30 days reported vaping because they enjoyed it (28%) and because they wanted to try it (24%).

- Among young adults aged 20 to 24 who reported having vaped in the past 30 days, the most commonly reported reasons for vaping were because they enjoyed it (27%); to reduce stress (25%); or to reduce, quit or avoid returning to smoking (24%).

- Over half of Canadians aged 25 and older who reported having vaped in the past 30 days reported vaping to reduce, quit or avoid returning to smoking (58%) as their main reason, while another 14% reported vaping because they enjoyed it.

Populations of Concern

People who smoke and vape (dual use), people who formerly smoked and now vape, pregnant people, people living with a mental health problem or illness, and young people are vulnerable to increased risks.

People who smoke and vape (dual use)

Some people try to quit or cut back on smoking cigarettes by vaping while continuing to smoke some cigarettes. This is called “dual use.” Dual use can turn into a troubling pattern because some people who vape may be supplementing smoking instead of replacing it. [6]

There are concerns that dual use can suppress efforts to quit smoking completely. [7] Even if a person cuts down the number of cigarettes smoked, there is no safe level of smoking. However, vaping is likely a less harmful option than smoking if the person switches completely. The end goal should always be to quit vaping too because using e-cigarettes can lead to a continued nicotine addiction, inhaling harmful substances (albeit less than smoking), and a risk of returning to smoking. [8]

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) recommends that health care providers advise people who are both smoking and vaping to switch completely from smoking cigarettes to vaping only. [9] For people who have quit smoking but are currently vaping, healthcare providers can encourage them to quit vaping. [9] People who don’t smoke, shouldn’t start vaping. [10]

People who formerly smoked and now vape

There is also a concern that people who formerly smoked and now vape might be at an increased risk of returning to smoking combustible tobacco cigarettes. [11] CAMH recommends that healthcare providers discuss both the risks (including relapse to using tobacco cigarettes and nicotine withdrawal) and benefits of quitting vaping with their clients. [9] All clients who formerly smoked and are advised to quit vaping should be monitored for relapse to smoking cigarettes. [9]

Pregnant people

The safety of vaping has not been established in pregnancy. Many studies have shown that nicotine use by people who are pregnant can affect a baby’s developing brain, lungs, and other organs. [12] Flavourings and other additives may also be harmful as they contain chemicals, some known to be cancer-causing. [13]

According to CAMH’s guidance, healthcare providers are advised to take a client-centered approach and discuss all treatment options so that clients can make an informed decision about pharmaceutical options. [9] Unfortunately, there is currently no agreement on a recommended pharmacotherapy strategy for people who are pregnant and want to quit vaping. [9]

People living with a mental health problem or illness

While nicotine has not been found to directly cause mental health problems, peer-reviewed studies reveal concerning links between vaping, nicotine, and worsening symptoms of depression and anxiety. [14] Studies have also shown that people who currently use e-cigarettes have double the odds of having a diagnosis of depression compared to those who have never vaped, and that nicotine use is significantly associated with higher levels of conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). [14]

A Cochrane review found that people who stopped smoking for at least 6 weeks experienced decreased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to people who continued to smoke. People who quit also experienced more positive feelings and better psychological wellbeing. [15]

Young people

Faced with declines in cigarette use, the tobacco industry expanded its products to include modern, colourful, flavoured nicotine-containing products to attract youth. [16] Evidence shows that the top reasons for trying vaping among youth are curiosity and to reduce stress. [17] This is a concerning trend as youth are especially vulnerable to the effects of nicotine, which can alter their brain development, affecting memory, concentration, and self-regulation. [1] This may also predispose them to dependence to nicotine as well as other substances. [18]

Youth Access

Among youth aged 15 to 19 who used a vape in the past 30 days, most (55%) reported accessing devices from social sources. Social sources included buying from a friend or family member, asking someone else to buy the vape for them, and having a friend or family member give or lend them the vape. [17]

Schools are heavily affected by the vaping issue as many students vape on school premises. The problem has proven difficult to curb as vaping devices are easily concealed, and the aerosol they produce doesn’t set off fire alarms. Many schools have reached out to public health and enforcement authorities in need of support and resources to help manage the vaping epidemic.

We all have a role to play in helping youth make informed decisions about the use of vaping products. The EOHU’s conversation starters about vaping webpage is a helpful resource with information you can use to have ongoing meaningful discussions with young people about the effects of vaping.

Vaping Cessation Guidance

Vaping for smoking cessation

The evidence is mixed regarding vaping for the purpose of smoking cessation. Vaping may be a harm reduction approach for people wanting to quit smoking. However, there is strong concern that the harm reduction benefits don’t outweigh the harms increased among young people who have never smoked and who begin vaping.

The industry’s claimed goal of harm reduction with vaping products is unconvincing as young people are targeted by product development and marketing – rather than people who smoke. Could it be a harm reduction product? Maybe. But the people experiencing the most harm are young people who have never smoked. The harms to young people are not acceptable even if vaping helps some adults who want to quit smoking.

A Cochrane review found that e-cigarettes with nicotine help people to quit smoking better than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) . [19] This same review also found that e-cigarettes with nicotine increase quit rates compared to e-cigarettes without nicotine. [19] However, the ideal length of treatment is not known. To date, no vaping products have been approved as therapeutics (cessation aids) in Canada. [1]

People who have quit smoking but are currently vaping, are encouraged to quit vaping as well.

Vaping cessation

Because vaping is a relatively new trend, more evidence is needed to support effective vaping cessation interventions. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) has developed a Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource meant to guide healthcare providers in supporting their clients who want to quit vaping. This guidance can be used by other non-clinical professionals as well.

The recommendations available in the guidance document are largely based on interventions adapted from tobacco cessation and are based on the evidence and expertise in the field at the time it was developed. Therefore, given the limited evidence, the recommendations are meant to provide general guidance only. There is also no clinical algorithm or guidance that currently exists for the use of NRT products in vaping cessation. More research is needed to determine the effectiveness of tailored cessation interventions and treatment for vaping. CAMH also released a document entitled Pharmacotherapy Recommendations for Vaping Cessation. This document can be a great tool for those assisting someone to quit vaping as it shares considerations and pharmacotherapy recommendations.

In non-clinical settings (e.g., schools), brief contact interventions can be beneficial to assist people in quitting vaping. Brief contact interventions are practices aimed at investigating a potential problem in a short interaction with an individual. It involves opportunistic advice, discussion, negotiation, and encouragement that can take as little as 5 to 10 minutes. An ideal framework for this is the 3 As model – ask, advise, act. Motivational interviewing can also be a helpful technique for longer interactions.

Regardless of the setting, it is important to note that all healthcare providers or allies should always use a person-centered approach when assisting individuals who want to quit vaping. [9] In the following section, helpful tools to facilitate a conversation on vaping cessation will be discussed.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is an approach that aims to reduce the negative impacts associated with the use of a substance (i.e., nicotine). When supporting an individual who chooses to use nicotine, refer to the Lower-Risk Nicotine Use Guidelines (LRNUG) to help them learn how to reduce risks to their health.

Vaping Cessation Tools and Techniques to Support Someone in Their Cessation Journey

As an ally, your goal should be to encourage an individual to move from the pre-contemplation to the contemplation stage within the stages of change model by linking them with education and tools to increase their confidence to change. The 5 stages of change include:

- Pre-contemplation: not thinking about quitting

- Contemplation: thinking about quitting, but not ready (considering quitting in the next 6 months or less)

- Preparation: getting ready to quit

- Action: quitting or reducing

- Maintenance: staying quit and avoiding relapse

The tools and techniques that can be helpful in accomplishing the transition between the stages of change are below.

5As (used in clinical settings) or 3As (used in non-clinical settings)

5As – Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange (or 3As – Ask, Advise, Act) is the most commonly used brief intervention framework for cessation. This framework guides interactions by laying out the steps a clinician or ally can take to identify people who smoke or vape and to address their use.

- Ask about their tobacco/vape use. Identify and document their tobacco/vape status.

- Example: “Do you smoke/vape?” If yes, “Would you be willing to talk a few minutes about your smoking/vaping?”

- Advise any person who uses tobacco/vapes to quit using a clear and non-judgmental approach.

- Example: “The most important thing you can do to improve your health is to quit smoking/vaping and I can help.”

- Assess willingness to quit now.

- Example: “Are you willing to quit or make an attempt within the next month if I help you?”

- Assist the person who uses tobacco/vapes with a quit plan. Use SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-based) objectives when creating the individualized plan. Provide or refer for behavioural counseling or additional services as needed.

- Arrange follow-up with the individual. Monitor challenges and progress.

- Example: “How are you dealing with cravings and stressful situations?” or “Have you had any slips or started smoking/vaping again?”

- Act on the person’s response. Build their confidence and support them with making a quit attempt using available cessation supports and referring appropriately for additional services.

- Quash app for youth 14 to 19 years old – Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Health Connect Ontario at 1 866 797-0000 or 811 for telephone support, fax referral form

- Smokers’ Helpline for online and text support

- Stop Vaping Challenge app for youth – Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Crush the Crave app for young adults – Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Not An Experiment Quit Plan for young people

Motivational Interviewing

When an individual wants to make a behavioural change, motivational interviewing techniques are necessary skills that any healthcare provider or ally should familiarize themselves with.

Motivational Interviewing is an “empathic, person-centered counseling approach that prepares people for change by helping them resolve ambivalence, enhance intrinsic motivation, and build confidence to change.” (Kraybill & Morrison, 2007)

Open questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summary reflections (OARS) are the basic interaction techniques and skills that are used in the motivational interviewing approach.

OARS technique:

- Open-ended questions: Allows the client/individual to do most of the talking.

Examples:- How can I help you with ____?

- What have you tried before to make a change?

- What do you want to do next?

- Affirmations: Helps build rapport and validate and support the individual in their process.

Examples:- I appreciate that you are willing to meet with me today.

- That’s a good suggestion.

- Reflections: Rephrasing a statement to capture the meaning.

Examples:- So, you feel…

- It sounds like you…

- Summarize: Ensures mutual understanding of the discussion and helps point out discrepancies between the individual’s current situation and future goals.

The practice of motivational interviewing requires the healthcare provider or ally to develop five primary skills:

- Express empathy: Be non-judgmental, listen reflectively, and see the world through the individual’s eyes. Understanding the individual’s experience can facilitate change.

- Develop discrepancy: Help the individual perceive difference between present behavior and desired lifestyle change. An individual is more motivated to change if they see that what they’re currently doing will not lead them to a future goal.

- Avoid argumentation: Gently diffuse individual defensiveness. Confronting their denial can lead to drop out and relapse. The healthcare provider should change their approach if the individual demonstrates that they are resistant to change.

- Roll with resistance: Reframe the individual’s thinking/statements, invite them to examine new perspectives and value themselves as being their own change agent.

- Support self-efficacy: Provide hope, increase the individual’s self-confidence in their ability to change behavior, and highlight other areas where they have been successful.

Motivational interviewing can be used to encourage continued quit smoking/vaping attempts. It may take several attempts to quit for good. With each attempt, lessons are learned, and strategies can be built upon and optimized to increase a person’s likelihood to remain smoke- or vape-free.

Readiness ruler

Another helpful tool to assess an individual’s motivation to change is the readiness ruler. Readiness rulers are designed to elicit change talk. Use them to explore the importance individuals attach to changing, as well as their confidence and readiness to change (on a scale of 1 to 10).

Examples:

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is it for you to quit vaping? (10 being very important)

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident are you that you can quit vaping? (10 being very confident)

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how ready are you to quit vaping? (10 being most ready)

Quit Plan

A quit plan is a set of steps an individual can take to prepare for a behavioural change (i.e., reducing or quitting vaping). The development of a quit plan and putting it into action can make the process of quitting easier and increase an individual’s chance of success. There are several elements to include in a quit plan:

- Knowing their reasons for quitting

- Setting SMART (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timely) goals

- How to deal with triggers and cravings/coping strategies

- How to deal with withdrawal symptoms

- Using nicotine replacement therapy products

- Relapse prevention strategies

- Supports

An individual can optimize their plan by going back to it and altering it as needed. Some quit plans (e.g., booklet, app) are available on the EOHU’s Tobacco Cessation Programs and Services webpage.

The E-cigarette Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (e-FTCD)

The E-cigarette Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (e-FTCD) is an assessment tool that was designed to help determine an individual’s level of dependence on nicotine. It has been adapted from the validated Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD). Assessment tools for electronic cigarette use can be found here.

Additional Resources

Resources for healthcare professionals to help your clients quit vaping:

- Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource (CAMH)

- Vaping Assessment Tools (CAMH)

- Lower-Risk Nicotine Use Guidelines (CAMH)

- You Can Make It Happen – Information for health professionals

- Don’t Quit Quitting – Website with tips and tricks to help quit

- Don’t Quit Quitting – Training video on Brief Contact Intervention

Resources for allies to help youth and young adults quit vaping:

- Conversation Starters About Vaping (EOHU)

- Vaping: What secondary school educators need to know (School Mental Health Ontario and CAMH)

- Vaping: What elementary school educators need to know (School Mental Health Ontario and CAMH)

- Consider the consequences of vaping (Health Canada)

- Blueprint for Action: Preventing substance-related harms among youth through a Comprehensive School Health approach (Public Health Agency of Canada)

- Not An Experiment (Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit)

- Vaping Education Resources (OPHEA)

Resources for people who want to quit vaping:

- Quash (Lung Health Foundation) Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Health Connect Ontario at 1 866 797-0000 or 811 for telephone support, fax referral form

- Smokers’ Helpline for online and text support

- Stop Vaping Challenge (Ontario Tobacco Research Unit) Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Crush the Crave Apple iOS devices | Android devices

- Not an experiment Quit Plan

- EOHU’s Tobacco Cessation Programs and Services

Further Training Opportunities

- Quash – Become a Facilitator/Adult Ally (Lung Health Foundation)

- TEACH – Training Enhancement in Applied Counselling and Health (CAMH)

Additional Information

References

- Government of Canada, "Risks of Vaping," 01 May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/vaping/risks.html.

- Smokefree.gov, "Stress & Smoking," [Online]. Available: https://smokefree.gov/challenges-when-quitting/stress/stress-smoking. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Truth Initiative, "Nicotine Use and Stress," 01 March 2022. [Online]. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/sites/default/files/media/files/2022/03/Nicotine%20Use%20and%20Stress_FINAL.pdf.

- C. Pisinger and M. Døssing, "A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes," Preventive Medicine, vol. 69, pp. 248-260, 2014.

- N. L. Benowitz and A. D. Burbank, "Cardiovascular toxicity of nicotine: Implications for electronic cigarette use," Trends Cardiovasc Med, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 515-523, 2016.

- A. P. Klein, K. Yarbrough and J. W. Cole, "Stroke, Smoking and Vaping: The No-Good, the Bad and the Ugly," Ann Public Health Res, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 1104, 2021.

- Truth Initiative, "E-cigarettes: Facts, stats and regulations," 15 June 2021. [Online]. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/e-cigarettes-facts-stats-and-regulations. [Accessed 01 May 2023].

- Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, "Adult Smoking Cessation—The Use of E-Cigarettes," 23 January 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/2020-smoking-cessation/fact-sheets/adult-smoking-cessation-e-cigarettes-use/index.html. [Accessed 01 May 2023].

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, "Vaping Cessation Guidance Resource," February 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/en/Documents/Vaping%20Cessation%20Guidance%20Resource.pdf. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Government of Canada, "Vaping and quitting smoking," 17 February 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/vaping/quit-smoking.html. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- L. A. Barufaldi, R. L. Guerra, R. d. C. R. d. Albuquerque, A. Nascimento, R. D. Chança, M. C. d. Souza and L. M. d. Almeida, "Risk of smoking relapse with the use of electronic cigarettes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of longitudinal studies," Tobacco Prevention & Cessation, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 1-10, 2021.

- B. D. Holbrook, "The effects of nicotine on human fetal development," Birth Defects Research (Part C), vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 181-192, 2016.

- Mayo Clinic, "Is vaping during pregnancy OK?," 24 March 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/pregnancy-week-by-week/expert-answers/vaping-during-pregnancy/faq-20462062. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Truth Initiative, "3 ways vaping affects mental health," 10 September 2021. [Online]. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/targeted-communities/3-ways-vaping-affects-mental-health. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Cochrane, "Featured Review: Stopping smoking is linked to improved mental health," 09 March 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.cochrane.org/news/featured-review-stopping-smoking-linked-improved-mental-health. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Truth Initiative, "How the tobacco industry’s new products could be leading to more nicotine addiction," 23 May 2022. [Online]. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/how-tobacco-industrys-new-products-could-be-leading. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Government of Canada, "Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS): summary of results for 2020," 01 April 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2020-summary.html. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- Drug Free Kids Canada, "Youth and Vaping – a growing trend," [Online]. Available: https://www.drugfreekidscanada.org/issues/vaping/. [Accessed 09 May 2023].

- J. Hartmann-Boycea, N. Lindsona, A. R. Butler, H. McRobbie, C. Bullen, R. Begh, A. Theodoulou, C. Notley, N. A. Rigotti, T. Turner, T. R. Fanshawe and P. Hajek, "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation," Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 11, 2022.